The Claim of a 'Slavery Compromise'

This article is part of the wealth tax series.

The Bernie Sanders for President website, not surprisingly, advocates for a wealth tax. He says a wealth tax would be Constitutional and uses several articles to support his view written by legal experts.

One piece of evidence the site substantially quotes is an article written in 2011 by Bruce Ackerman and Anne Alstott. They insist the clause, “capitation and other direct taxes,” was written as some sort of compromise for the slave-holding South. But this is simply not true.

The clause they appear to quote is from Article II, Section 9. The draft at that point during the Constitutional Convention just began with, “No capitation tax shall be laid…” An amendment to the clause was made and it became, “No capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid…” This was on September 14, 1787 and it had nothing to do with slavery.

They may have been referring to Article I, Section 2 where clause 3 begins, “Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several States...”1 This was the area of the draft where the debate regarding House representation and direct tax apportionment centered.

The “Compromise”

The article postulates that the provision, direct taxes shall be apportioned, was part of a compromise with the southern states. Its purpose, according to the authors, was to prevent a head (capitation) tax on slaves because such a tax isn’t possible to apportion. There are two fallacies here: the compromise and the purpose. First up is the compromise claim.

In Organic Wealth, I describe direct taxes and apportionment from the Constitutional Convention debate in detail. To summarize, the main focus of the debate was how to determine each state’s representation in the House of Representatives. Would it be based on population numbers or on the wealth of each state? Those who argued wealth thought since they would contribute more in taxes, they should have more voting power.

Eventually, the delegates agreed that representation would be based on population while at the same time restraining direct taxation to population too. That way, a wealthier state with a smaller population wouldn’t be out-voted to impose unfair direct taxes against its citizens.

As a part of that larger debate, arose the issue regarding counting slaves. Would they be counted to determine the population of each state? If so, then southern states with slaves would have an advantage in House representation and it would encourage even more slavery, which many from the Convention objected to. On the other hand, slaves contributed to wealth creation and also increased the South’s contribution to any direct taxation.

Here are some key points in chronological order:

July 12, 17872

Mr. Morris moved to vary the representation in the House according to the principles of wealth and numbers of inhabitants (including slaves). He proposed the provision, “that taxation shall be in proportion to representation.”

There was an objection that it would lead to requisitioning the States for revenue. As a result, the rule was then changed to restrain taxation to only direct taxation. The approved provision: “provided always that direct taxation ought to be proportioned to representation.”

Mr. Davie then spoke out saying the southern states wouldn’t receive any representation for their slaves and that South Carolina wouldn’t agree to the Constitution unless slaves were counted for representation as three fifths.

Mr. Randolph urged that slaves be included in the ratio of representation as three fifths. Madison writes, “He (Randolph) lamented that such a species of property existed; but, as it did exist, the holders of it would require this security.”

Mr. Wilson thought less people would object to slaves being included in the rule of representation, if they were only an indirect ingredient to the rule. He proposed changing the provision by reversing it: “provided always that the representation ought to be proportioned according to direct taxation.”

Wilson’s idea meant they would calculate the proportion of direct taxation first, which would include counting slaves, then base House representation on that proportional number.

July 24, 17873

Mr. Morris wanted to remove the clause proportioning direct taxation to representation. He had only meant it as a bridge.

September 13, 17874

Mr. Dickinson and Mr. Wilson moved to remove “and direct taxes” from article I, section 2 believing it to be misplaced as a part of section 2.

Mr. Morris pointed out that the insertion here (section 2) was in consequence of what had passed to this point. They didn’t want the appearance of counting the slaves as part of the representation. The including of them, though, allows them to be seen as being counted for direct taxation purposes, and only as a by-product to that of representation.

The motion by Dickinson and Wilson was defeated so now what appears in the Constitution are two clauses that deal with apportionment from Article I. They are in sections 2 and 9.

The final version of the Constitution doesn’t link representation to direct taxation or vice versa. It just says that both need to be apportioned. James Madison doesn’t note this final change, but maybe Mr. Morris’s bridge mentioned on July 24th (linking the two) was indeed the catalyst for the removal. The issue was resolved with the three fifths rule for slaves for both representation and direct taxation.

The original sin, of course, was slavery, but the compromise that actually occurred relevant to slaves was counting them as 3/5 of a person. This was the compromise which is detestable, not the bigger idea of apportionment. The provision of direct taxation requiring apportionment had nothing to do with slavery. Its purpose was to raise revenue for times of emergency while protecting the wealth from within each state.

In fact, the counting of slaves was more relevant to House representation and not direct taxes. Would the authors of this article claim we should rid ourselves of the House of Representatives because of this initial debate over the counting of the slaves?

The “Purpose”

The authors then claim the purpose of direct taxes requiring apportionment was to prevent a head (capitation) tax on slaves, which would be impossible to apportion.

The problem is there was no such thing in these debates to even support the existence of such a tax. No one advocated for taxing slave owners based on the number of slaves they had. If they did, it wouldn’t be called a capitation tax, but a slave tax. Capitation taxes of the time fell on everyone equally who were the objects of the tax. A slave tax doesn’t fit this description.

In Organic Wealth I offer the opinion the income tax most resembles a modern capitation tax and not an excise as Courts have decided. Pick up a copy to learn why capitation works best. It doesn’t fall on everyone equally, but based on their ability to pay.

What Compromise?

To further prove my points, on May 29, 17875 a plan for a federal constitution was submitted early on in the Convention. The segment of interest said:

“The proportion of direct taxation shall be regulated by the whole number of inhabitants of every description… No tax shall be laid on articles exported from the states; nor capitation tax, but in proportion to the census before directed.”

The idea of limiting direct taxation, including capitations, to a census of each state (apportionment) was envisioned before any debate on the wording of the Constitution had even begun, let alone any compromise. And, it included the whole number of all inhabitants, which includes the slaves as whole persons, which would work against the South because they would pay more with direct taxation.

The article’s claim that apportionment for direct taxes had to do with some slavery compromise with the South is ludicrous.

You may conclude these professors are incompetent, but I don’t believe so. There are many more legal experts with similar published articles all over the internet. They’re not all inept. I think the real reason is to sway the American public into believing a wealth tax is Constitutional. Then, when Democrats have enough power to stack the Supreme Court with activist justices and not ones with judicial restraint, they can pass a wealth tax without public outcry.

Another False Claim

The article also says an 1895 Court declared the income tax to be unconstitutional. Then, afterward, with better judgment, the ruling was superseded by the 16th Amendment.

The fact is the Springer v. United States (1880) found the income tax to be Constitutional. The 1895 Pollock case didn’t address employment income (deferring to Springer) but rather, taxes on property and the income from property such as dividends and bond yields. The Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 was ruled unconstitutional in Pollock because the Act taxed income from property. The Sixteenth ensured that income from all sources could be taxed without apportionment.

They assert the Pollock Court was using the “slavery compromise” to justify their ruling that the income tax was unconstitutional. This judgment then forced Congress and the States to enact the 16th Amendment having used much better moral clarity.

Their conclusion: “Given this history, it is extremely unlikely that the justices will cite the founders’ original compromise with slavery to bar a tax that would serve the cause of economic equality and democratic legitimacy.”

The problem with their conclusion is everything they claim is false. Therefore, justices will have no problem citing truth and not made up facts which are promoted in this article.

You can read more about the wealth tax in these articles:

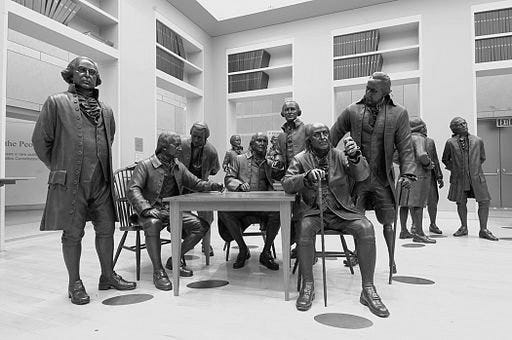

Image by Elliot Schwartz for StudioEIS / CC BY-SA

Article I. (n.d.)., from https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/articlei

Online Library of Liberty. (n.d.)., from https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1909#Elliot_1314-05_2980

Online Library of Liberty. (n.d.)., from https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1909#Elliot_1314-05_3448

Online Library of Liberty. (n.d.)., from https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1909#Elliot_1314-05_5649

Online Library of Liberty. (n.d.)., from https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1909#Elliot_1314-05_1929